Advice for building a career as a freelance artist

and/or paid cartoonist

by Dave Roman

Having worked at Nickelodeon Magazine for 11 years, I’ve done countless portfolio reviews, classroom visits, alumni events for the School of Visual Arts and other art-based institutions. The following is a compilation of things I usually end up talking about in regards to finding work in the comics and illustration fields. Hopefully some of it will come across as helpful! Most of it relates to my specific perspective as an editor who works with and hires other artists mixed with anecdotal evidence from co-workers and friends in the industry. But some things are just my personal opinion!

What kind of illustrator are you?

For any one assignment there are thousands of artists that could potentially be hired. Why should an editor or art director hire you? You need to figure out what makes your art unique. Because when there are a thousand artists who would all like the same gig, often just being good isn’t enough. You have to have a distinctive voice. It’s not about whether you can draw a bowl of fruit, it’s about how bad-ass, or realistic, or cute you can draw that fruit and convince people that no one has ever drawn it that way before. This sometimes gets confused with “the hot style,” but really it comes down to making art that lots of people find appealing and want to see more of. Figure out what your strengths are and what adjectives people use to describe the way you draw. Is it elegant, surreal, old-fashioned, cute, edgy, hip, classy, pretty, dynamic, dramatic, soft, hard, or all of the above? You may not want to categorize yourself, but to a certain extent you will need to if you want to focus yourself and find the places that will actually hire you.

Make the most of your location.

Most people don’t NEED to move to a major city like New York or Los Angeles to get paying illustration or comics work. Freelancers can work from home studios, so it doesn’t really matter where they are located.

But you’ll probably need the following:

-A high-speed Internet account.

-E-mail that can receive and send large files (up to 10 megs).

-A decent scanner (with good optical resolution for print reproduction).

-Adobe PhotoShop and Adobe Acrobat on your computer.

-Access to a local Fed-Ex or DHL drop-off (sometimes found within a Staples or Kinko’s store).

- An FTP program like Fetch, Transmit, or Cyberduck (you can find free trial versions online).

If you work from home and know you are going to be vacationing near a specific company, arrange to meet up with an editor or an art director in person. Adding a face and friendly personality to a familiar name and art style will always help you in the long run.

Keep in mind that people who live closer to the companies they work for (or want to work for) have the added benefit of being able to drop off stuff in person, regularly meet their editors face to face, be invited out to business lunches, etc. So they will always have an advantage over freelancers who live far away.

In New York City there are hundreds of book and magazine publishers, newspapers, design firms, commercial producers, TV stations, and web companies that all use freelance illustrators. With many of these places, you can email or call someone to find out when the best day is to drop off a traditional portfolio for them to look through. They’ll then let you know when to come by and pick it up. They may leave a note, or rejection slip, or request to see more samples, or hire you. But if you don’t try you’ll never know for sure.

Compile a portfolio.

When you send or show a portfolio to an editor or potential client, be sure to include only your BEST WORK. Ideally, that work should look “finished” or print-ready. Including a few samples of art that you’ve actually had printed somewhere (like a zine, comic, local magazine, etc.) is always a good idea. It helps editors visualize what your art will look like in THEIR magazine if they can see how it turned out in someone else’s. Always have a level of confidence in what you do. If you have to apologize for anything in your portfolio, you shouldn’t have included it.

Organize your portfolio.

It shouldn’t be a random sampling of what you think are your coolest drawings. Your portfolio should be tightly focused on selling you not just as an artist, but specifically, as an illustrator for hire. The artwork that you choose should be your most “bankable,” by which I mean, it should covey how you could be used to draw specific things for specific people. Editors for magazines that focus on electronics or business like Wired, Fortune, Mac Life, and so on, need lots of spot illustrations of people at computers, talking on cell phones, and walking with briefcases on busy sidewalks, as well as graphs and charts. So if your portfolio is made up of cute animals, country houses, and landscapes, they probably won’t think you are the best fit for them. Some editors can be shortsighted, but often it’s simple practicality. They might assume that even though you didn’t include any drawings of computers, it doesn’t mean you can’t draw them…but the deadline might not permit the time it would take to find out. So make sure there is clearly discernable SUBJECT MATTER in every drawing you choose. And then make sure there is a diversity of that content in the portfolio.

Having a variety of CONTENT and SUBJECT MATTER to your work is more important than a variety of STYLES.

If you have 3 drawings of elves battling in Middle Earth, balance it out with some real people and day-to-day environments.

Don’t draw the same character in 10 different poses with no backgrounds.

Include some color.

Unless you only want to be a superhero comic book penciller, make sure there are color as well as black and white samples in your portfolio.

If you don’t know how to color digitally, LEARN IMMEDIATELY.

Adobe PhotoShop is the industry standard for coloring comics, and pretty much digital illustration in general. Some art directors won’t even have a conversation with you if you tell them you only use any other art program.

Learn the difference between files created for the web and files for print BEFORE you get hired on a professional job. You don’t need to know how to do everything there is to know in PhotoShop. Just become familiar enough that you are at least comfortable scanning your art, cleaning your files, and coloring them in a way that is suitable for high-quality printing. You can find lots of tutorials online that teach how to color comics and basic illustrations. Once you’ve mastered that, you’re all set. No one person knows what every single tool, setting and option in PhotoShop does–just learn what you need to make the program work for your art needs.

It’s cool to learn how to use other art programs, especially ones that specialize in certain skill sets like Painter, or Manga Studio, but you will still NEED to learn PhotoShop if you want to be a versatile freelancer. And if you really want to be even more bankable, learn at least a basic understanding of Adobe Illustrator (for vector-based illustrations–which are more and more in demand) and Adobe InDesign (the industry standard in print layout/design programs).

Don’t overwhelm editors with too much material.

Always include the URL to your website and ask about sending additional samples of you work via the web. Usually, artists interested in illustration assignments will make up 1 – 3 postcards of what they think are their strongest pieces. Even if an editor doesn’t think an artist is ready to hire, they might keep your samples on file in case something comes up. The needs of editors and art directors are constantly changing–you could be exactly what they need a year from now. In the meantime, rather than waiting around for phone calls, you should be constantly working to improve and diversify your portfolio. Some editors will take the time to tell you what they don’t like about your samples or point you in a specific direction. Try not to be insulted, and listen to what they tell you! They might be open to you re-submitting if they see you’ve actually paid attention. But if you ignore them and just send more of the same, you can pretty much guarantee they will throw your stuff in the trash.

Promote yourself with…

A website.

ANY website is better than no website. So don’t wait 5 years to come up with the most original design in the world or wait to be able to afford a great hosting plan. Get something up quick, even if it’s on one of the many free hosting services. Then you can perfect the site in your spare time and re-upload it when it’s done. Don’t let style weigh over substance. If a website is too hard to navigate or doesn’t make clear where the illustration gallery section is located, an editor might give up before they find out.

Most important is making sure your e-mail address is in an easy-to-find location on the site! Additional contact information is always welcome, too. In America, professionals don’t usually hide behind an alias. Don’t be afraid to use your real name!

When you have a website you are happy with, make sure it has an easy-to-remember URL. Buying your own, unique domain name doesn’t cost too much (about $10 a year) and you can often just pay for a forwarding service if you don’t want to also pay for additional website hosting.

You web address doesn’t have to be THAT creative.

www.yourfirstandlastname.com can often be the perfect URL when it comes to getting freelance work. This goes for choosing an email address as well. yourrealname@yahoo.com or mail@yourwebsitename.com is a lot better than xdemonsux@aol.com or hotstudcartoonist@earthlink.net.

Update your website regularly with a balance of your new and BEST work.

The most popular artists are constantly producing new material and have sketchblogs in addition to the main gallery on their sites. Editors will check in from time to time (or subscribe to RSS feeds) to see what artists are up to.

I personally keep a folder on my desktop with cool illustrations I come across on the web, along with the name of the artist (if I can clearly figure that out!).

Free gallery sites like DeviantArt, ComicSpace, MySpace, etc. are a great way to get your feet wet. These sites are especially good for networking with other artists, trading criticism and getting a sense of what people respond to in your art.

But when you are serious about being a professional (especially for print and publishing) it’s important to get your own gallery site going too–a site that is strictly for the stuff you’d want an art director to see (no funny comments and links from friends) and has the features mentioned above.

Business cards.

Still an integral part of networking and getting yourself work. There’s no reason not to have one. You can buy pre-folded business card paper at Office Max and run it through a home printer, or even have the copy center run them off for you. In fact most Staples/Office Max/Office Depot copy centers have a business card ordering service that can make you really nice cards very cheaply. You can even provide them with artwork, or design them completely yourself and hand them a disk. There are also lots of affordable printing places online like overnightprints.com that will print 100 full color cards for $10 and ship them to you in less than week.

The reason that there is a STANDARD BUSINESS CARD SIZE is so that people won’t lose them.

If they don’t fit in a wallet or rolodex, they are too big. If they fall out of business card pockets in wallets, they are too small. Small cards are becoming trendy in the alternative comic scene, and I’ve already lost plenty of them.

Make sure the writing on your card is legible and includes your name, email address and website URL.

I think phone numbers are optional nowadays, but it never hurts to include one if you really want an editor to call you. You can include titles like “Artist,” “Cartoonist,” “Illustrator,” and even “Writer, Artist, Designer,” but don’t try to show off or risk coming across as a Jack of All Trades/Master of None. Focus on what you do best, or what you want to do MOST. It’s always a good idea to have a sample of your art on the card to help remind people why they have your business card in the first place!

Postcards featuring your artwork.

This is more affordable than ever. There are hundreds of printshops both local and online that will print full-color cards affordably. Usually 500 cards is plenty.

Once you have some cards you’ll want to make a list of people and places you can send them to. Sometimes other illustrators or organizations will share their lists with you, which can be a huge time saver. But they may not always be up to date and there’s something to be said for an artist who takes the time to find out exactly where they want to work and contacts them directly. Most magazines have mastheads with addresses or info about where you can send stuff. Usually you want to send your postcards to an art director, designer, or editor whose name seems to be associated with a lot of illustrators you like or know.

What editors/designers will do with your postcards can really vary. If I get a postcard I like, I’ll tack it to my wall or add it to a pile on my messy desk. I’ve seen art directors and designers who keep large folders full of postcards for when they want to try something new, while others dismiss every card they get. I admittedly throw away cards that don’t impress me. But I’ve also passed along cards to other editors who they might better suit.

Get your work published.

It doesn’t even matter where. Just having something in a printed magazine or book shows that, if nothing else, you were able to meet some deadline, work to spec, basically do what was needed to get something done. Even if it’s a self-published zine/mini-comic, that still puts you a step ahead of someone who doesn’t know how to adapt their artwork for the printed page. There are a lot of uber-talented artists out there who cannot follow simple instructions. Lots of editors would rather avoid working with them if possible, and go with someone they know won’t need “hand-holding.”

If you can get your work published somewhere extremely visible like a magazine, newspaper, or art anthology, there’s more of a chance an editor will come across your work and feel as though they “discovered” you. Because not everyone wants to be the first person to publish a unique artist, but lots of people would love to be the second. Editors, art directors, and product people all look at comics anthologies as a resource for inspiration and a place to find new artists to try out when the right project comes up. I tend to keep these books near my desk at work specifically for this purpose. Sometimes a co-worker will ask me to recommend someone for an art-related job and I’ll have them flip though things like Flight, Meathaus, Scatterbrain, MOME, Life Meter, or whatever, and see if anything impresses them or helps us narrow down exactly what art style we are looking for. I’ve visited lots of other media companies and seen copies of comics anthologies on their shelves for the same reason.

**If you can’t figure out how to get into a pre-existing anthology…start your own!

Additional promotion online.

Your artwork can never be seen in too many places. MySpace, ComicSpace, Livejournal, Blogspot, DeviantArt, Facebook. An artist can have all of the above, and whatever new networking sites pop up in the future. Different people will come across your work in different ways and that’s a good thing. You can create separate accounts for dating and social networking if you want to keep that stuff separate, or want a private place to post art that you don’t want to rest of the world to see and discover you through.

Narrow the focus on where you want to get published.

Go to Barnes and Noble, Hudson News, or any place with a really diverse magazine selection. Flip through every magazine, even the ones you think you have no interest in. Look at them specifically for the illustrations, to get a sense of what kind of artists different magazines like to use. See if you can find ones that you think compliment your own art style(s). Look at the beginning of the magazine for the masthead to see if there is an address, or information about submissions. Usually the assistant art directors/editors are going to be the best people to contact. Sometimes there’s a main e-mail address, but they will forward your request to the most relevant person. This same approach can be used for comics publishers. See who is publishing the kinds of artists you relate to and target them first.

With book and comic publishers, it’s best to contact them one at a time rather than submitting the same material to various places.

If you don’t get the types of assignments you want at first, don’t give up.

KEEP DRAWING, keep pushing yourself. Don’t be afraid to take on some less glamorous gigs just to get your stuff out there. You never know where things can lead. And having a body of work is really good!

If you get a gig, make sure you complete it.

Quitting in the middle of a job is the most unprofessional thing you can do. Even if it’s torture, follow it through to the end! You will be stronger for it. And the sooner you can finish it, the better!

Arguing with someone who hires you is pointless.

If they ask you to change something, you have to do it–even if you don’t agree with the change. That’s why they are PAYING you. Complain to your friends and family all you want. But do whatever it takes to finish the job first. I’ve had to fire artists in the middle of big multi-page assignments because they had too many issues, constantly questioned the notes, or were just stubborn about having to pick up a pencil again. As an artist myself, I am usually sympathetic and try to make my freelancers’ lives easier whenever possible. But if I’m juggling too many stressful deadlines I can lose patience like anyone else, opting to continue with someone more flexible and easy to work with. I have freelancers who have redrawn entire characters or panels over several times because of wishy-washy editors or outside requests from legal departments of corporate heads–and they actually do so enthusiastically, and say things like “these changes have made the comic so much better now.” I’m sure the artist secretly hates my guts and wished that they got everything perfect the first time, but the fact that she/he UNDERSTANDS THAT THIS IS A JOB and is willing to do what we ask with a smile on their face (or email) makes me want to pay them lots and lots of money and recommend said artist to every person in the world. Mark Crilley, Scott Roberts, Jeff Albrecht, Stu Chaifetz, and Wes Dzioba, are examples of such artists. I hire them any change I get!

Don’t be a jerk.

The art industry is a small world. Things get around. If you are unpleasant to work with, you can guarantee that an editor will warn others. Godlike-talent can overcome blacklisting, but it’s an uphill battle. So don’t be afraid to take a little criticism about your work. It is a huge part of the business. And be ready to make any and all changes someone asks you to make. Usually, that’s part of the reason they are paying you. Editors expect to be allowed a reasonable amount of changes, especially in the sketch or rough draft stages. And yes, even in the final stages sometimes. It sucks, but it is a reality that you will not be able to avoid if you want to keep working.

Leave your studio every now and then.

Go to art gallery openings, author signings, and book release parties! Go to comic book conventions, especially ones with independent creators as the focus (like the MoCCA Art Fest, Small Press Expo, the Alternative Press Expo, S.P.A.C.E, STAPLE!, Stumptown, etc.). These types of events can be great networking opportunities. Even if you just end up talking to people in your exact same position, comparing notes can really help put you on the right path! Just be careful not to come across as forceful, desperate and/or conceited! Being relaxed and making a good impression is as important as everything else you do. Making friends is never a bad thing either!

Help spread goodwill.

Showing support for your fellow artists is always time well spent. You’re helping to invest into a future where you hope to be on the other side of the table someday. Buy the works from the artists you think are great and spread the love to friends and family. Be passionate about the industry you want to be a part of. Volunteer for or join art support groups like the Graphic Artist Guild, Society of Illustrators, Cartoon Allies, The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Friends of Lulu, The National Cartoonists Society, the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art, and so on. Even if you don’t live in a major city you can probably find other like-minded people who you can team up with. Many people start weekly local comics jams, or have mini-comic folding and stapling parties to combine being social with creating and improving their art. Nowadays people also do these kinds of things online by forming/joining Livejournal communities, participating in drawing-based message boards, websites, podcasts, etc. Seek them out and introduce yourself. Make friends, not arguments!

Positive energy is infectious.

People who truly care about the art and craft of comics, illustration, movies, etc. are the ones who seem to rise to the surface. Like the Divine Comedy song says, “You have got to love what you do!”

Everyone enjoys working with people who have upbeat, optimistic attitudes. If you’re always complaining about this thing or that thing, it can really add up and paint you as someone with a bad attitude. Even people who are sympathetic to what you are complaining about can get tired of it and decide they’d rather not surround themselves with negativity. So do everything you can to avoid being known as the guy who complains about everything. Take a chill pill, get a massage, listen to a rock song that will cheer you up. We all know that life sucks and then you die. But the people who accept it, move on, and smile in the face of annoyance, are the ones that get the most out of their lives and careers. All of the most successful people in the industry have survived some really horrible crap at one point or other.

Remember that the internet can help your career, or destroy it.

The “don’t be a jerk” rule definitely applies online. Sometimes more so, because you can’t always recognize the inflection or context of a comment to know if it was tongue-in-cheek. Editors read message boards and check out blogs just like everyone else. Talking bad about people can come back to haunt you. I know plenty of editors who refuse to hire people based on things they saw them write online several years ago. It’s not about holding grudges as much as not being able to wash the bad taste out of your mouth.

Dealing with rejection.

If you keep getting rejected you’ll need to look more critically at your style and content, as well as your abilities. Start asking for real opinions from other artists to figure out what the next step needs to be. What works for one artist won’t work for everyone. And for some people the road to reaching your potential can be a lot longer.

Don’t be surprised if you still have to live with your parents for a while.

Full-time jobs in the art industry can be hard to come by, especially if you don’t live in a major city. One of the most reliable recipes for finding one, though, is through internships. It’s as close to a sure thing that exists in helping your career; even more so than art school. Lots of companies use internships as training grounds for new employees. And even if a company can’t hire you, they are probably more likely to recommend you to someone who can–but only if you show them that you are someone worth doing so for. That usually means giving it your all, with enthusiasm and an eagerness to work (especially for no money).

Most people get great paying jobs AFTER they’ve worked for free.

The easiest way to get an internship is through school. But some companies are willing to take in recent college graduates if they are eager enough. You can always call and ask if a company offers any kind of internship or mentoring program. If they don’t, ask if they can recommend any places that do. Doing free illustrations for non-profit companies and local organizations is also a good way to get your art out there and build up your portfolio with some printed samples.

***But be careful of people looking to take advantage of young artists by having you create lots of free work on spec. Always ask for the opinions of other artists you trust before you take on a job that you feel nervous about. You gotta know when to say no!

***Be careful of signing a contract that seems shady! Never be afraid to ask for advice from smart people before you sign something you are unsure about. Even if you don’t have an agent or a lawyer, you probably know someone who is smart enough and understands legal speak enough to know when you might be taken advantage of.

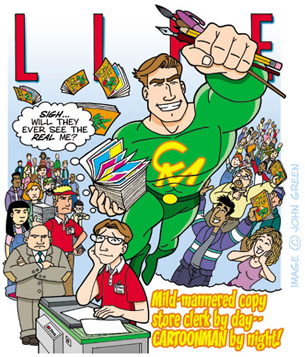

Keep your day job…for now.

Lots of famous and not-so-famous artists have “regular” jobs to pay the bills during slow gaps in illustration work. Don’t be embarrassed or let that get you down. Keep working on your stuff, improving your portfolio and adding to your list of clients.

And most of all: create art that makes you happy!

I worked for several years at a copy shop job because it gave me access to and discounts on copy services, which encouraged me to produce my own mini-comics. I knew that as long as I had a creative outlet for my ideas I could be content working anywhere.

Being a professional is a state of mind.

And being an artist doesn’t mean you have to make all your money from drawing all the time. It just means you are putting all your heart into what you create and sharing it with the world on a regular basis.

SVA and other art schools.

Does having a specific school like the School of Visual Arts (SVA) or Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) on a resume open doors? It certainly never hurts. And both are great schools with fantastic cartooning programs. But nothing on a resume is a sure thing with art.

The work of the artist really has to speak louder than words. The school you graduate from is a great point of reference that will hopefully lead to lots of worthwhile conversations and comparing of war stories. That said, if you are looking for an art-RELATED job, and the employer also went to the same school, they might connect with you quicker. As an editor, I’m always willing to give an SVA grad an extra shot. But it never guarantees I’ll throw work their way if there is someone better for the job.

The great thing about SVA is that most of the teachers are working professionals. So you can really pick their brains about actually working in the field. And if you hit it off, they might invite you to parties/gallery openings and introduce you to different people who can introduce you to other people who could end up hiring you. It’s often a chain of events (sometimes seemingly unrelated at first) that can lead to a gig. And at the end of the day it’s all about who you know. SVA and other art schools allow for you to get to know people, but only if you really take the time to make that happen. And obviously without the right combination of personality, ability, and ambition–it’s hard to say what will happen.

I commuted from Long Island to NYC for two out of my four years at SVA and worked a part-time job on the weekends, for half that time. It was tough, and I wished I had lived closer to school so I could spend more time drawing and less time on the train. Art school (and I’m sure college in general) is all about what you put into it. And the more time you can devote to working the more you will learn and grow as an artist. I think people can grow as artists without art school. But it certainly helps to force you to do things you might normally put off, and kicks your ass in ways you would never think of on your own.

Anyway, these are just my opinions. I’m sure a lot of people who read this can contradict pretty much every point with some other theory! But, this is my two cents.

(c) Dave Roman 2007